Season two of the Accused podcast focuses on the murder investigation of Retha Welch. Welch, a religious recovering addict who used her free time to minister prison inmates, was found stabbed and beaten in her Newport, Kentucky apartment in April of 1987. Police soon focused in on William Virgil, a former inmate whom Welch had counseled, as their main suspect.

Virgil was convicted of Retha Welch’s murder in 1988 due in large part to Joe Womack’s testimony. Womack, housed in solitary confinement near Virgil for a short period of time, testified that Virgil had confessed the crime to him. The conviction was secured because he mentioned details of the crime that were not yet released to the public. Following his conviction, William Virgil was sentenced to seventy years in prison.

Later, Joe Womack would tell officials that his testimony in the 1988 trial was completely untrue. He admitted that he and Virgil were not given the opportunity to speak to each other while in solitary confinement; therefore, he never heard Virgil confess to the crime. Womack claimed that the details of the murder were fed to him by law enforcement, who went so far as to provide him with a “cheat sheet” of the fabricated account in preparation for his 1988 testimony.

In 1988, Joe Womack was 23-years-old. He was a first time criminal and he was terrified. Although Womack told the jury that he was not receiving any sort of incentive for testifying, he now admits that police coerced him with money and the promise of parole.

In 2013, with help of attorneys from the Innocence Project, the court approved DNA testing on evidence recovered from Welch’s murder scene. In 2016, Joe Womack recanted his testimony. In 2017, the prosecution dismissed the charges against William Virgil due to lack of evidence. After 28 years in prison, Virgil is now a free man.

Incentivized Informants

The story of William Virgil and Joe Womack is anecdotal evidence of a very real phenomenon: a 2004 study by Center on Wrongful Convictions revealed that incentivized witnesses are the leading cause of wrongful convictions in US capital cases. The Innocence Project reports that incentivized witness testimony was critical to the conviction in 15% of cases that have been overturned by DNA evidence.

Incentivized informants are individuals who stand to benefit by offering an incriminating testimony. These informants, often times fellow inmates, are negatively referred to as “jailhouse snitches”. In the vast majority of instances, inmates are not sought out to give a manufactured testimony as in the case of Joe Womack; they become informants by their own fruition for their own gain.

Jailhouse informants are normally inmates who are awaiting trial or sentencing. For most, the benefits greatly outweigh the risk. If an inmate makes the decision to lie on the stand, he or she could be criminally prosecuted for perjury. However, if the testimony is deemed credible, the informant could be rewarded with a lesser sentence, a favorable recommendation for parole, or even money. The benefits are so compelling that some inmates testify in multiple, separate cases.

Make no mistake- the money offered to witnesses is not just a few bucks for goods at the commissary. In some counties and states, informants are offered thousands for information. Two prisoners in southern California made over $300,000 between 2011 and 2015 for informing on fellow inmates.

A reduced sentence can be just as- if not more- alluring than money for jailhouse informants. Inmates will go to great lengths to secure information that could potentially lead to less time behind bars. Take Bruce Lisker’s case, for example.

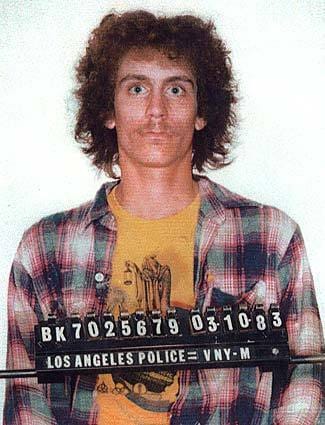

On March 10, 1983, 17-year-old Bruce Lisker came home to find his mother, Dorka Lisker, had been stabbed and beaten. Lisker was high on meth at the time and, when the police arrived, was covered in blood due to his attempts to revive his deceased mother. A few days later, Bruce was arrested and taken to a juvenile facility. After the court decided that Lisker would be tried as an adult, he was moved to Los Angeles County Jail.

Within days of the move, two men came forward to police claiming that Lisker had confessed to the murder. These men were quickly dismissed by law enforcement as liars. During that time, Lisker had struck up a friendship with the men housed in the cell next to his. They spoke through holes in the walls between the two cells, and they formed a sort of prayer circle. One day, an inmate whispered to Lisker that he might be able to help prove his innocence. Claiming that he had resources on the outside, the man requested a copy of the police report. Lisker obliged, and passed the report to the man through the hole.

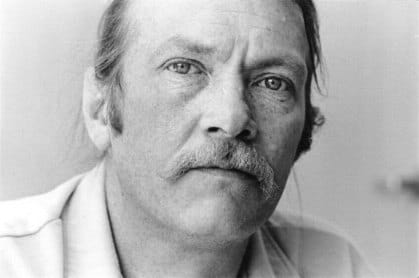

That man was 29-year-old Robert Donald Hughes. Based on notes found on the police report, Hughes was able to craft a convincing story about the murder of Dorka Lisker. He came forward to officials claiming that Bruce Lisker had confessed the crime to him. Based on the cause of death found on the report, Hughes told police that Lisker admitted to bludgeoning his mother because she found him rifling through her purse. Despite conflicting physical evidence found at the scene of the crime, Hughes’s testimony helped to secure Lisker’s conviction. That testimony earned Hughes a reduced sentence, and caused an innocent man to spend 26 years in prison.

Incentivized informants agree to testify due to a well-established system of reciprocity. The “I’ll scratch your back if you scratch mine” agreement is not limited to pre-determined conditions. Sometimes, the “back scratch” is not defined or even promised. Some inmates choose to provide information for the mere prospect of favorable treatment in the future.

Diversion

Incentivized informants are not just inmates with nothing to lose. The Innocence Project reports that murderers seize the opportunity to “snitch” in order to cast suspicion away from themselves. This is perfectly illustrated by the murder investigation of William Dulan.

Dulan, an 88-year-old retired farmer, was murdered in his Sheldon, IL home. Hours after the crime, known cocaine addict Gayle Potter was arrested for attempting to cash a check in his name. Potter was trapped and desperate during her interrogation with police; to take the blame off of herself, she implicated Joseph Burrows and Ralph Frye.

The two men were brought in and questioned by police. With an IQ of only 75, Frye was extremely susceptible to coercive police interrogation tactics. After a lengthy interview, Frye admitted that he helped Joseph Burrows murder William Dulan. There was no physical evidence to suggest that Burrows and Frye committed the crime. Additionally, four witnesses placed Joseph Burrows sixty miles away from Sheldon at the time of the murder. Despite these facts, Potter and Frye’s testimonies secured Burrows’s conviction. Frye and Potter plead guilty to 23 and 30 years in prison, respectively. Burrows was sentenced to death.

Two years later, Gayle Potter and Ralph Frye recanted their statements. The prosecution dismissed the charges against Joseph Burrows, and he is now a free man. Now we know that Gayle Potter alone was responsible for the murder of William Dulan. It was only to avoid the death penalty that Potter implicated Burrows and Frye.

Reform

During the Sophonow Inquiry, Canadian Commissioner Cory said, “Jailhouse informants comprise the most deceitful and deceptive group of witnesses known to frequent the courts. The more notorious the case, the greater the number of prospective informants.” Incentivized witness testimonies yield an alarming amount of wrongful convictions. The use of jailhouse and other incentivized informants is- in a word- problematic.

The American Bar Association recommends that these types of testimonies be excluded from use in the courtroom. The Innocence Project and other wrongful conviction advocacy groups argue for reform. The groups argue for heavy regulation so that incentives are not hidden, improper testimony is not told to the jury as fact, and the judge has the authority and obligation to instruct jurors on the unreliability of such testimony.

If such regulation existed, would Joseph Burrows, Bruce Lisker, and William Virgil have wasted decades of their lives in prison? If incentivized testimonies were excluded, would the juries still have found these men guilty beyond a reasonable doubt? We may never know what could have happened if it were not for unreliable informants, but we can learn from the mistakes of our past

If you or a loved one have been charged with a crime, please contact the attorneys at Rehmeyer & Allatt for a free consultation.